I’ve been talking about the need for a tool to transition from “move things around the little window by the code” teaching tools like Scratch, Khan Academy coding and Greenfoot. These are all great ways to start kids coding, but they are walled-off playgrounds with no connection to the outside world or even the rest of the computer you’re working on. Is there an accessible tool that allows students to easily do visually interesting things but also gives them access to code that can read and write files, create and connect to databases, and get data off the internet? And then I thought, what was that Java IDE that Sun made back in the 90s with a form builder, is that still around? And so I found myself at Netbeans.org.

I’ve been talking about the need for a tool to transition from “move things around the little window by the code” teaching tools like Scratch, Khan Academy coding and Greenfoot. These are all great ways to start kids coding, but they are walled-off playgrounds with no connection to the outside world or even the rest of the computer you’re working on. Is there an accessible tool that allows students to easily do visually interesting things but also gives them access to code that can read and write files, create and connect to databases, and get data off the internet? And then I thought, what was that Java IDE that Sun made back in the 90s with a form builder, is that still around? And so I found myself at Netbeans.org.

Netbeans is anything but a new tool; at 20 or so years old it’s practically geriatric by tech standards. When Netbeans came out Yahoo was the exciting new search engine, Mark Zuckerberg was a working on a media player as a high school project and a large percentage of internet sessions began with loud scratchy modem handshakes to AOL. I feared finding a neglected and forgotten product today, but Netbeans is quite up to date; the standard download comes with JDK 8 and tools for creating pages in Swing or JavaFX, the newer user interface module.

Netbeans is anything but a new tool; at 20 or so years old it’s practically geriatric by tech standards. When Netbeans came out Yahoo was the exciting new search engine, Mark Zuckerberg was a working on a media player as a high school project and a large percentage of internet sessions began with loud scratchy modem handshakes to AOL. I feared finding a neglected and forgotten product today, but Netbeans is quite up to date; the standard download comes with JDK 8 and tools for creating pages in Swing or JavaFX, the newer user interface module.

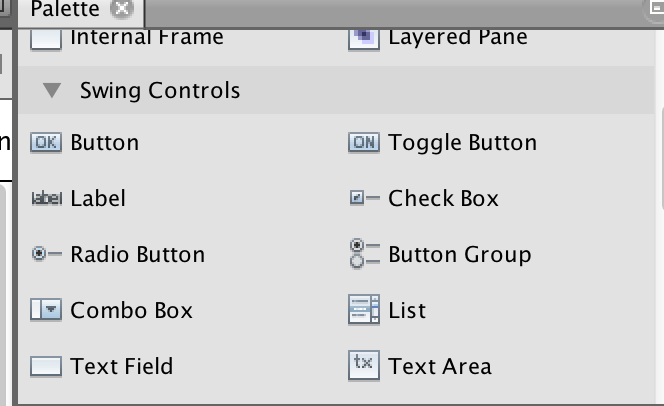

Don’t get me wrong; to do anything in NetBeans you have to know Java. So how does it help? The main way is that it makes creating user interfaces with Swing ridiculously easy using the forms design. To make a window you just select-click on your project, choose new and then choose JFrame form. You’ll see the window in the design view, and to your right you have a bunch of different UI elements like text boxes, buttons, checkboxes and so on that you can drag and drop right on your frame.

Programming the UI is equally easy. To make an event listener for an element (that’s the code that happens when the button’s clicked or element’s changed or whatever), just double click on the element. You’ll be right  in the event listener class, so you can just write the code you want it to perform. (You can see more details in my first NetBeans lesson on my YouTube channel).

in the event listener class, so you can just write the code you want it to perform. (You can see more details in my first NetBeans lesson on my YouTube channel).

As I said, you’ll still have to know Java to do actually make the code in the listener, but with NetBeans your students can focus entirely on what they want their code to do rather than dealing with the the clunky Swing UI code or remembering the difference between addGroup() or addContainerGap().

But wait there’s more! NetBeans also makes it easy to create an Entity Class from Database. That means if you have a database connection you can easily make the students connect and start doing SQL commands with Java. It also allows you to create a Web Service Client. I’m not saying either of these are things kids could figure out on their own, but if you do the heavy lifting on the backend you can have kids do some serious programming with data that is not in a little box by the code window.

After I got excited about this, I immediately discovered that Oracle is planning on turning NB over to the Apache foundation as an open source project, and a sinking feeling filled my gut. I had experienced something similar before, when I got excited about teaching Microsoft’s fabulous XNA gaming platform in C# right before Microsoft dropped it like a used wad of gum. XNA became Monogame, but at least at the time Monogame was not what XNA had been. So I know well enough that “it’s becoming an open source project” is often the software industry’s equivalent of your parents telling you “the dog is on a beautiful farm where he can run and play all day.”

After I got excited about this, I immediately discovered that Oracle is planning on turning NB over to the Apache foundation as an open source project, and a sinking feeling filled my gut. I had experienced something similar before, when I got excited about teaching Microsoft’s fabulous XNA gaming platform in C# right before Microsoft dropped it like a used wad of gum. XNA became Monogame, but at least at the time Monogame was not what XNA had been. So I know well enough that “it’s becoming an open source project” is often the software industry’s equivalent of your parents telling you “the dog is on a beautiful farm where he can run and play all day.”

But Apache is not just any open source foundation; they are behind the most popular *NIX web server and Mozilla one of the most popular browsers – which you may well be viewing this page on – among many other projects like the Thunderbird mail app.

Even more encouraging was the thriving community of NetBeans developers I’ve discovered on Twitter. According to the NetBeans team there are more than a million users of NetBeans today, meaning a lot of commitment to keeping it alive and thriving. I wonder if these people realize NB’s potential as a learning tool for younger students?

I’m not going to get into the debate over whether NetBeans is better than Eclipse. Clearly some developers feel it is, but many more prefer the great purple circle (or one of the other popular IDEs like IntelliJ), and Eclipse may indeed be better for a commercial EE developer. For new students, however, it’s extremely intimidating with not a lot of handholds and no help with sorting out a parallelGroup from a sequentialGroup or a verticalGroup when you’re making a UI.

I’m experimenting now with NB as a teaching tool for students as young as 8th graders. I’ll continue to keep the blog up to date on how it works, and be sure to check out my NetBeans playlist on YouTube as it grows.

I love teaching kids to make video games. I’ve done this for quite awhile now, using a lot of different languages, including Python, Scratch, the

I love teaching kids to make video games. I’ve done this for quite awhile now, using a lot of different languages, including Python, Scratch, the  doodle around and do the same thing over and over, and a smaller number of kids push against the limits of the platform. This can lead to some incredibly ugly code in a limited platforms – I’ve seen people build a scrolling platformer with Scratch, but it’s like painting your house with a nail polish brush, and the code is about as attractive. Other platforms have less of a ceiling; Greenfoot contains within it the full capabilities of Java, so theoretically you can do anything, but it’s a huge stretch to get from making a single-screen game with limited sprites and objectives to the sort of games kids imagine, with things like scrolling, jumping with gravity-like motion or different kinds of 3D.

doodle around and do the same thing over and over, and a smaller number of kids push against the limits of the platform. This can lead to some incredibly ugly code in a limited platforms – I’ve seen people build a scrolling platformer with Scratch, but it’s like painting your house with a nail polish brush, and the code is about as attractive. Other platforms have less of a ceiling; Greenfoot contains within it the full capabilities of Java, so theoretically you can do anything, but it’s a huge stretch to get from making a single-screen game with limited sprites and objectives to the sort of games kids imagine, with things like scrolling, jumping with gravity-like motion or different kinds of 3D. Physical computing, such as working with Arduinos, is definitely an area of potential here. I will be working with students making Arduino projects this year, and I’ll report on how it goes. As with games, physical computing involves working with things that are interesting learning tools in an of themselves but are not actually programming. More significantly, most Arduino programs, at least of the sort students do, are very simple, and may not touch on many advanced concepts. The difficult part of physical programming is usually the physical part. And anyways, you aren’t always in an electronics lab; sometimes you just have the computers to program with. So what else can you do?

Physical computing, such as working with Arduinos, is definitely an area of potential here. I will be working with students making Arduino projects this year, and I’ll report on how it goes. As with games, physical computing involves working with things that are interesting learning tools in an of themselves but are not actually programming. More significantly, most Arduino programs, at least of the sort students do, are very simple, and may not touch on many advanced concepts. The difficult part of physical programming is usually the physical part. And anyways, you aren’t always in an electronics lab; sometimes you just have the computers to program with. So what else can you do? I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and it came to me the other day: students really need to do is work with data. Real data, not the Northwind database or fake lists of names from the phone book. Data about the real world, like climate records, health surveys, demographic information, data that allows them to address real problems in the world. But where do they get the data? And how do we get it in a format that they can work with it?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and it came to me the other day: students really need to do is work with data. Real data, not the Northwind database or fake lists of names from the phone book. Data about the real world, like climate records, health surveys, demographic information, data that allows them to address real problems in the world. But where do they get the data? And how do we get it in a format that they can work with it?