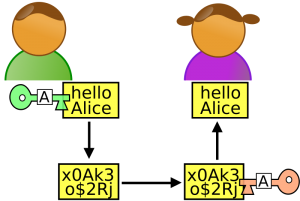

Recently I’ve been having students play around with some “toy” encryption programs, mostly simple double-Caesar encryptions, which is a good way to learn about text in Java. As with everything I started thinking and reading about encryption, and came to a terrifying realization: encryption for regular people is doomed.

Recently I’ve been having students play around with some “toy” encryption programs, mostly simple double-Caesar encryptions, which is a good way to learn about text in Java. As with everything I started thinking and reading about encryption, and came to a terrifying realization: encryption for regular people is doomed.

About 25 years ago a coder named Phil Zimmerman invented an algorithm that has become central to the net. It was modestly named Pretty Good Privacy, but it was a method of encryption that was free, usable by pretty much anyone, and almost completely uncrackable by pretty  much anyone, even the US government. It was based on a relatively simple mathematical principle: if you have a factor of two very big prime numbers (where ‘very big’ is at least 40 decimal digits, though for modern implementations more likely 150 or 300 digits) it’s almost impossible find those factors. Specifically, for a regular fast processor it would take millions of years of trials; a huge multi-core supercomputer might get it done in your lifetime but it would take years and the computer couldn’t be doing anything else.

much anyone, even the US government. It was based on a relatively simple mathematical principle: if you have a factor of two very big prime numbers (where ‘very big’ is at least 40 decimal digits, though for modern implementations more likely 150 or 300 digits) it’s almost impossible find those factors. Specifically, for a regular fast processor it would take millions of years of trials; a huge multi-core supercomputer might get it done in your lifetime but it would take years and the computer couldn’t be doing anything else.

As with so much about info tech it’s easy to forget how revolutionary this was. Before that, really good encryption was only really available to big governments and maybe corporations. I’m not really sure what encryption methods they had; probably they already had a prime-based method similar to PGP, but I don’t know

. Now it was available to everyone in the country, and pretty soon the world as method predictably spread beyond our borders (as Zimmerman, an anti-nuclear activist, certainly intended it to). The US government freaked out almost immediately, and by 1993 Zimmerman was being prosecuted. Zimmerman c leverly published the code as a hardback book, which was indisputably protected by the First Amendment. Later court cases over similar encryption methods established the principle that code is protected by the First as well.

leverly published the code as a hardback book, which was indisputably protected by the First Amendment. Later court cases over similar encryption methods established the principle that code is protected by the First as well.

Even if the government had succeeded in prosecuting Zimmerman it would have done nothing to put the genie back into the bottle. The basic algorithm was easy to program and implement by any  talented coder, and soon was. Many other encryption algorithms have since been invented using some variation of Zimmerman’s prime number hack. PGP is still around as well; most recently Ed Snowden used a more advanced version of PGP to share his whistleblowing documents with Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras as documented in Poitras’ intense documentary Citizen4.

talented coder, and soon was. Many other encryption algorithms have since been invented using some variation of Zimmerman’s prime number hack. PGP is still around as well; most recently Ed Snowden used a more advanced version of PGP to share his whistleblowing documents with Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras as documented in Poitras’ intense documentary Citizen4.

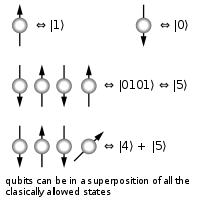

In 1980 physicist Richard Feynman proposed the concept of storing computer data not as ones as zeroes as people had done so far (and still almost entirely do) but as “qubits,” or quantum states of two-state quantum systems. In 1985 David Deutsch speculated in a theoretical paper about using these to make a computer that would solve at least some problems at a speed many many orders of magnitude faster than even the fastest digital machines.

In 1994 Peter Schor proposed a method for factoring large integers using this method in what algorithmic specialists would call “polynomial time,” as opposed to the “exponential time” it currently required. This is an extreme simplification, but to explain the difference between polynomial and exponential time consider a program that has to solve a problem with a “length” of 100 parts. In exponential time the program would have to solve a number of operations equal to 100 to some power, so say 100 to the 5th power, or about 10 billion operations. That’s a big number to us, but an Intel i7 processor that does about 300,000 operations per second could do it in a few hours. Exponential time, by comparison, would mean something like 2 to the power of 100, which is a number with about 30 digits, which the same processor couldn’t finish in the lifetime of our solar system, and possibly the universe. These are completely made-up numbers but hopefully give some sense of the difference.

Lots of progress has been made in quantum computers, but as far as I know, no one has made a quantum computer that can execute Schor’s algorithm in that way. But you can be certain that the NSA and many other intelligence agencies are pouring an enormous amount of resources into solving this problem. In fact, if you were paying attention to the dates you might have noticed that Schor invented his algorithm within about a year of when charges were filed against Zimmerman for publishing PGP, so Schor certainly picked factoring large numbers as a challenging problem for a good reason.

Lots of progress has been made in quantum computers, but as far as I know, no one has made a quantum computer that can execute Schor’s algorithm in that way. But you can be certain that the NSA and many other intelligence agencies are pouring an enormous amount of resources into solving this problem. In fact, if you were paying attention to the dates you might have noticed that Schor invented his algorithm within about a year of when charges were filed against Zimmerman for publishing PGP, so Schor certainly picked factoring large numbers as a challenging problem for a good reason.

There’s no way to predict technological progress, so no way to know when or even if Schor’s Algorithm will be implementable on a practical level. But likely it will happen. Not everyone will be able to do it. Only people who can afford top-level quantum computers will be able to, which for a long time will only be available to large organizations like governments and big companies. In addition to offering a way to break current cryptography, quantum computers also offer a method of encrypting that can’t be broken by a quantum computer.

In other words, when Shor’s Algorithm can be implemented, we’ll be back where we were before PGP: good crypto will no longer be available for the average user. If the NSA had had this ability when Snowden was communicating with Greenwald and Poitras, they could potentially have decrypted their messages, learned who Snowden was, and arrested him before he escaped the country.

Okay, then, so no more Edward Snowdens; that sounds pretty bad. But it’s not even the start of the problem. In the 25 years since Zimmerman invented his algorithm, the web has become central not only to most people’s lives but also our economy. A huge amount of business is done online, and all of this must be encrypted. You might have noticed that addresses at the beginning of your url bar often begin with ‘https’ instead of ‘http’. This means that your communication with the server is encrypted using the RSA encryption scheme, which depends on uncrackable primes in the same way PGP does.  In the early 90s, encryption was for spies and hackers; now it’s essential to every person who uses the net. In fact, Google Chrome will soon warn users that sites using plain http are insecure.

In the early 90s, encryption was for spies and hackers; now it’s essential to every person who uses the net. In fact, Google Chrome will soon warn users that sites using plain http are insecure.

I don’t suppose the NSA has any interest in hacking Amazon to steal my credit card number. But foreign governments might want to, or a criminal organization that has enough money to buy their own quantum computers. No doubt the government will try to criminalize ownership of quantum tech, but it will almost certainly work no better than any other attempts they’ve made to keep a technological genie in the bottle. Currencies like Bitcoin that depend on strong crypto will become worthless, as will the vaunted “blockchains” that every cyber-libertarian is predicting will transform our world.

Furthermore our lives will become entirely transparent to anyone with the money and power to buy the tech to look. And they will certainly exploit this ability. True privacy on the web will become impossible.

Eventually, like all other tech, quantum computers will become affordable to regular people and we will again be able to have really uncrackable crypto. This likely will take at least a decade, and that’s assuming no one tries to prevent it, which governments likely will.

I don’t know what impact this is going to have on our world. But it’s a question not enough people are asking.

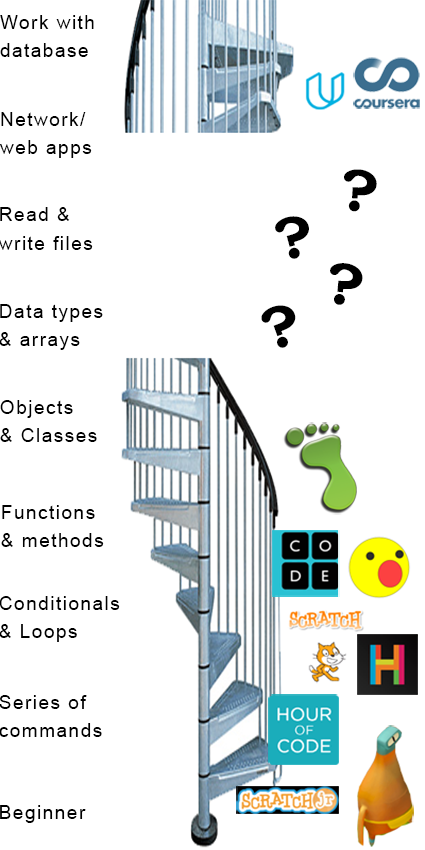

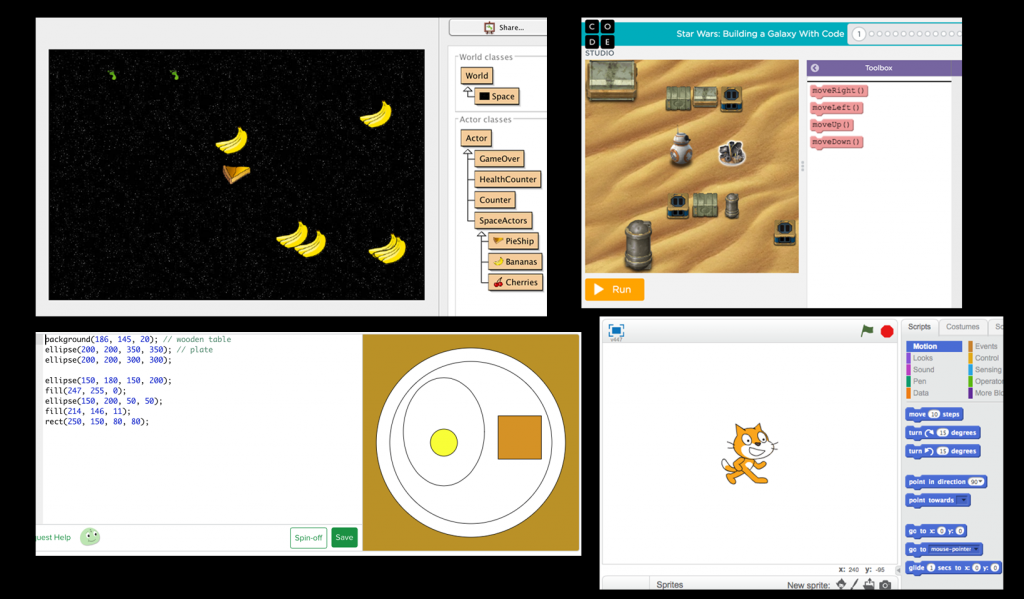

This is part of a series on what is the best first ‘pro’ language, meaning something that’s actually used for professional applications.

This is part of a series on what is the best first ‘pro’ language, meaning something that’s actually used for professional applications.  Every few months, it seems, everyone is excited about a new front-end “framework.” Frameworks are new downloadable modules of Javascript and CSS that come up with some (supposedly) better way of handling things in the DOM of various browsers. A few years ago everyone was using jQuery, which isn’t exactly a framework maybe but was an easy way to do a lot of visual things like dropdown menus and more importantly get fresh information from the server without loading a whole new page using AJAX. But Google had developed their own way to do that using a framework called Angular which is based on the Model View Controller web paradigm. At the same time Facebook developed a framework called React that wasn’t made for client-server interactions but which many people consider better than Angular for dealing with events in the user interface. Now Google has made Angular 2 which is very different from Angular.

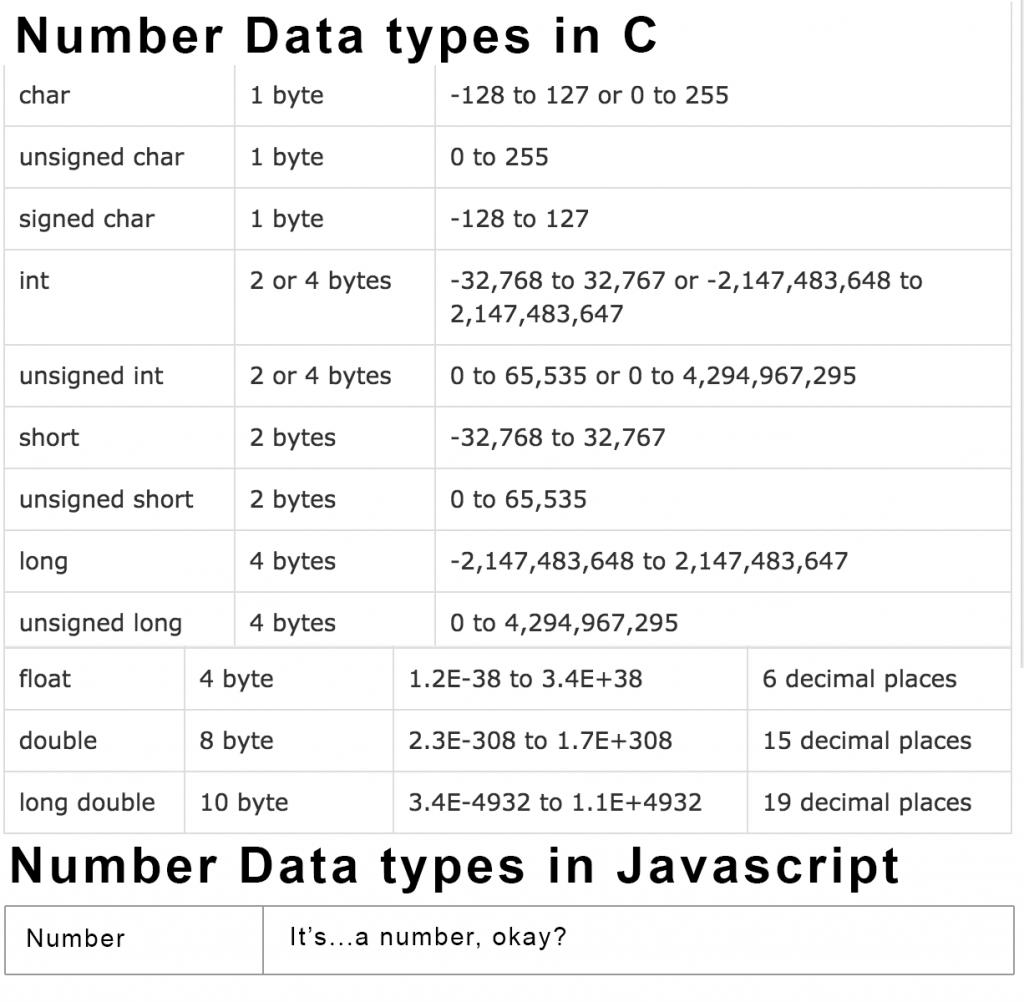

Every few months, it seems, everyone is excited about a new front-end “framework.” Frameworks are new downloadable modules of Javascript and CSS that come up with some (supposedly) better way of handling things in the DOM of various browsers. A few years ago everyone was using jQuery, which isn’t exactly a framework maybe but was an easy way to do a lot of visual things like dropdown menus and more importantly get fresh information from the server without loading a whole new page using AJAX. But Google had developed their own way to do that using a framework called Angular which is based on the Model View Controller web paradigm. At the same time Facebook developed a framework called React that wasn’t made for client-server interactions but which many people consider better than Angular for dealing with events in the user interface. Now Google has made Angular 2 which is very different from Angular. If you say x = 10 in Javascript then x’s datatype is…number. As far as JS is concerned x could become 87 billion or 0.0003. But as far as JS is concerned x could become the lyrics of the national anthem or a graphical DOM element. This is very, very far from the way a computer’s memory works, so when a student moves to a language that’s even implicitly typed like Python, let along statically typed like Java, they are going to be in for a terrible shock.

If you say x = 10 in Javascript then x’s datatype is…number. As far as JS is concerned x could become 87 billion or 0.0003. But as far as JS is concerned x could become the lyrics of the national anthem or a graphical DOM element. This is very, very far from the way a computer’s memory works, so when a student moves to a language that’s even implicitly typed like Python, let along statically typed like Java, they are going to be in for a terrible shock. I’ve

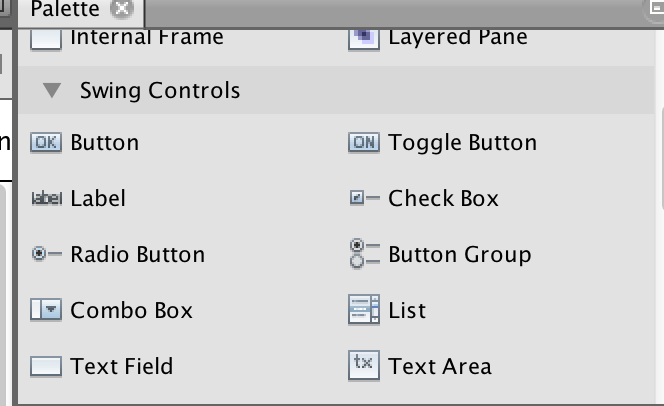

I’ve  Netbeans is anything but a new tool; at 20 or so years old it’s practically geriatric by tech standards. When Netbeans came out Yahoo was the exciting new search engine, Mark Zuckerberg was a working on a media player as a high school project and a large percentage of internet sessions began with loud scratchy modem handshakes to AOL. I feared finding a neglected and forgotten product today, but Netbeans is quite up to date; the standard download comes with JDK 8 and tools for creating pages in Swing or

Netbeans is anything but a new tool; at 20 or so years old it’s practically geriatric by tech standards. When Netbeans came out Yahoo was the exciting new search engine, Mark Zuckerberg was a working on a media player as a high school project and a large percentage of internet sessions began with loud scratchy modem handshakes to AOL. I feared finding a neglected and forgotten product today, but Netbeans is quite up to date; the standard download comes with JDK 8 and tools for creating pages in Swing or  in the event listener class, so you can just write the code you want it to perform. (You can see more details in my

in the event listener class, so you can just write the code you want it to perform. (You can see more details in my  After I got excited about this, I immediately discovered that Oracle is planning on turning NB over to the Apache foundation as an open source project, and a sinking feeling filled my gut. I had experienced something similar before, when I got excited about teaching Microsoft’s fabulous XNA gaming platform in C# right before Microsoft dropped it like a used wad of gum. XNA became

After I got excited about this, I immediately discovered that Oracle is planning on turning NB over to the Apache foundation as an open source project, and a sinking feeling filled my gut. I had experienced something similar before, when I got excited about teaching Microsoft’s fabulous XNA gaming platform in C# right before Microsoft dropped it like a used wad of gum. XNA became