Yesterday I got a message from a teacher on Twitter. She mostly teaches science but this year she’s supposed to teach a 9-week tech class. She said she was “not a techy but willing to learn” and asked me what I thought the kids should know by the time they are done. I was flattered to be asked, and it inspired me to write an answer I was happy with, especially the six things I think kids should learn in a tech class. Here’s a slightly modified version of what I wrote:

Thanks so much for asking this; it gives me a reason to re-think what I want my own students to learn. I started out thinking about specific concrete skills (using variables or understanding files, e tc.), but realized that those aren’t the most important things.

tc.), but realized that those aren’t the most important things.

The things that I think kids should learn from technology education are skills that all good programmers and engineers have, but aren’t specifically tech skills. Some of the main ones are:

- Think algorithmically: learn to plan out a sequence of steps that can solve a problem

- Break down a problem: separate it into smaller parts that are easier to solve than the original problem

- Debug independently: when a solution you have isn’t working, start testing smaller parts of the solution to see which part isn’t giving you the result you were expecting so you can hunt down the problem

- Modularize solutions: look for ways you can re-use parts of earlier solutions that worked in other problems

- Open-source your solutions: put your solution in a form that your peers can understand them and use different parts as needed.

- Import solutions into your own: when a peer has come up with a good way to solve a problem that’s part of the problem you’re working on, don’t re-invent the wheel. Use a modified version of their idea, while giving them credit of course.

Of course these are huge goals and not easy to impart to a student even if you have whole year with them, let alone 9 weeks. You didn’t say how many classes you have a week, but I’d focus on just a couple of them, maybe the first and second or first and third.

As for what specifically to do, this is challenging even if you are given clear goals, let alone if you don’t. I’m sure you already have, but the first thing I’d do is feel out the administration more to try to get a better idea of what they expect to come out of it.

Assuming they really don’t have a particular goal in mind, my advice is to be a little bit ambitious and aim for a target you might not achieve at least the first few times around. If you’re a Google Apps school, the students will learn how to use the apps in their other classes pretty quickly on their own. If this is the main focus of your class I predict they and you will be bored very soon.

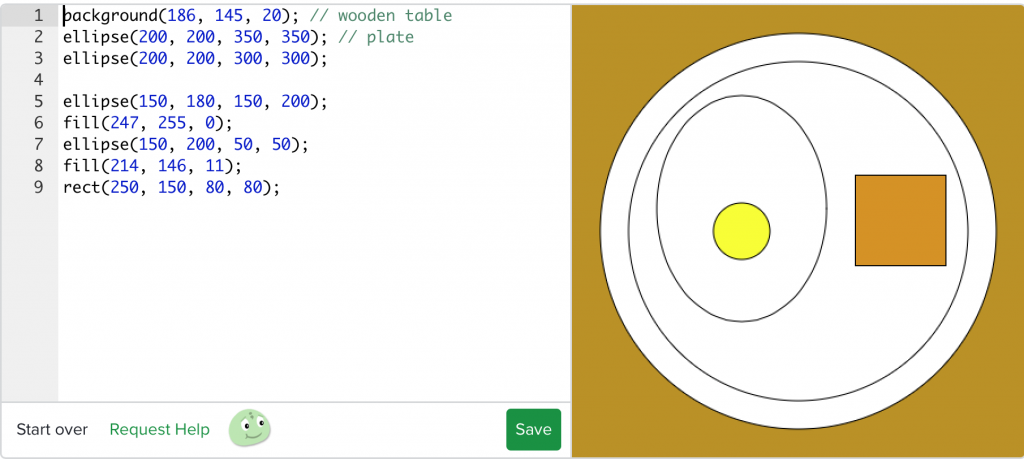

One of the things I highly recommend for this is the Khan Academy tech classes. It’s easy for the kids to log in with their Google Drive accounts and for you to create a class where you can monitor them. The classes are very self-directed, with videos accompanying an interactive programming window, so if students have headphones they can all proceed at a pace that works for them. As a teacher I’m sure you know that with any subject some students will take to it like a fish to water and others will have a great deal of difficulty. This is doubly true for programming.

One of the things I highly recommend for this is the Khan Academy tech classes. It’s easy for the kids to log in with their Google Drive accounts and for you to create a class where you can monitor them. The classes are very self-directed, with videos accompanying an interactive programming window, so if students have headphones they can all proceed at a pace that works for them. As a teacher I’m sure you know that with any subject some students will take to it like a fish to water and others will have a great deal of difficulty. This is doubly true for programming.

Some things you might have them learn are:

- Make a web page using HTML. You and they can learn how to do this at the Khan academy intro to hml/css lessons. If you have more time with them you can move on to the more advanced interactive web pages lessons.

- Learn to use Processing JS at the Khan Academy Intro to JS course.

- Teach them to manage databases with SQL at the Khan Academy SQL course.

If you continue to do this class and your school is willing to spend a little money (really very little) on some hardware, I’d recommend ordering some Arduinos from Adafruit. and teach kids to make some simple electronic devices such as these ones .

I love teaching kids to make video games. I’ve done this for quite awhile now, using a lot of different languages, including Python, Scratch, the

I love teaching kids to make video games. I’ve done this for quite awhile now, using a lot of different languages, including Python, Scratch, the  doodle around and do the same thing over and over, and a smaller number of kids push against the limits of the platform. This can lead to some incredibly ugly code in a limited platforms – I’ve seen people build a scrolling platformer with Scratch, but it’s like painting your house with a nail polish brush, and the code is about as attractive. Other platforms have less of a ceiling; Greenfoot contains within it the full capabilities of Java, so theoretically you can do anything, but it’s a huge stretch to get from making a single-screen game with limited sprites and objectives to the sort of games kids imagine, with things like scrolling, jumping with gravity-like motion or different kinds of 3D.

doodle around and do the same thing over and over, and a smaller number of kids push against the limits of the platform. This can lead to some incredibly ugly code in a limited platforms – I’ve seen people build a scrolling platformer with Scratch, but it’s like painting your house with a nail polish brush, and the code is about as attractive. Other platforms have less of a ceiling; Greenfoot contains within it the full capabilities of Java, so theoretically you can do anything, but it’s a huge stretch to get from making a single-screen game with limited sprites and objectives to the sort of games kids imagine, with things like scrolling, jumping with gravity-like motion or different kinds of 3D. Physical computing, such as working with Arduinos, is definitely an area of potential here. I will be working with students making Arduino projects this year, and I’ll report on how it goes. As with games, physical computing involves working with things that are interesting learning tools in an of themselves but are not actually programming. More significantly, most Arduino programs, at least of the sort students do, are very simple, and may not touch on many advanced concepts. The difficult part of physical programming is usually the physical part. And anyways, you aren’t always in an electronics lab; sometimes you just have the computers to program with. So what else can you do?

Physical computing, such as working with Arduinos, is definitely an area of potential here. I will be working with students making Arduino projects this year, and I’ll report on how it goes. As with games, physical computing involves working with things that are interesting learning tools in an of themselves but are not actually programming. More significantly, most Arduino programs, at least of the sort students do, are very simple, and may not touch on many advanced concepts. The difficult part of physical programming is usually the physical part. And anyways, you aren’t always in an electronics lab; sometimes you just have the computers to program with. So what else can you do? I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and it came to me the other day: students really need to do is work with data. Real data, not the Northwind database or fake lists of names from the phone book. Data about the real world, like climate records, health surveys, demographic information, data that allows them to address real problems in the world. But where do they get the data? And how do we get it in a format that they can work with it?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and it came to me the other day: students really need to do is work with data. Real data, not the Northwind database or fake lists of names from the phone book. Data about the real world, like climate records, health surveys, demographic information, data that allows them to address real problems in the world. But where do they get the data? And how do we get it in a format that they can work with it?